NASH/MASH Resources

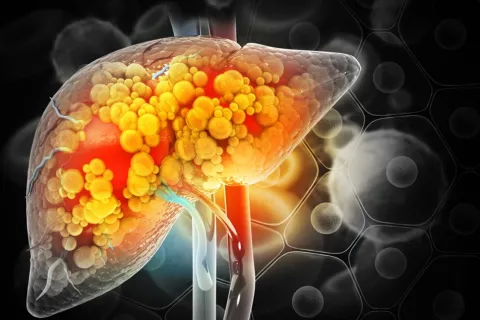

MASH is the new NASH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, is a form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, in which the liver is inflamed and damaged due to the buildup of fat in the liver.1 In June 2023, it was decided by patient and professional groups working with liver diseases to change the name of NASH to MASH. MASH stands for: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Similarly, NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) has changed its name to MASLD (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease). The name change was made because both “non-alcoholic” and “fatty” are terms associated with unhealthy lifestyle choices and may be stigmatizing. Additionally, clinicians and researchers felt that the new name better described the disease.2

The inflammation and liver damage from MASH can cause fibrosis and scarring and can lead to cirrhosis, where the liver is scarred and significantly damaged, often permanently. These severe, negative consequences can lead to end-stage liver disease, liver cancer, and even death.3 MASH is the fastest growing cause of liver transplant in the United States.4

MASH is also associated with cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. People with MASH are more likely to have cardiovascular disease and/or type 2 diabetes and vice versa. Cardiovascular disease, or CVD, is the leading cause of death in people who have MASH.5 Patients with MASH have been shown to be twice as likely to die from CVD as liver disease.6

Most patients with MASH are asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms in later stages of the disease.7,8 When and if those symptoms develop, they can include fatigue, fluid buildup, and the yellowing of the skin or eyes.9

An estimated 25%–30% of the United States population (aged ≥15 years) live with MASLD.7 Approximately 22 million adult Americans* are estimated to live with MASH.10 Of those, nearly 9 million individuals live with clinically significant liver disease (F2/F3).11,12,†

Diagnosis and staging of MASH remain linked to histology, however professional guidelines and practice guidance now recommend noninvasive tools (NITs) such as blood-based or imaging techniques to assess the likelihood of fibrosis and predict risk of disease progression.7

According to one estimate, in the United States, MASH is projected to affect 27 million people by 2030.10 During the same time period, the average total healthcare cost of MASH is projected to rise from $3537 per person to $4950 per person.13

MASH is responsible for high healthcare resource utilization and mortality.13,14

The costs and complications of MASH are shown below:

- Cirrhosis: ~$100,000 annually14,‡

- Hepatocellular carcinoma: ~$124,000 annually15,§

- Estimated average liver transplant in United States: $878,40016,||

- Cardiovascular-related deaths: ~228,750 expected to occur annually by 203010

- Liver-related deaths: 78,300 expected to occur annually by 203010

- Estimated total liver transplant costs in the US in 2023: $8.6 billion16,||

FIB-4 is a noninvasive test based on basic parameters, including patient age, liver enzymes, and platelet count. It can help risk stratify patients for liver fibrosis and advancement.7 A high FIB-4 is correlated with significantly increased medical costs. According to 1 analysis,¶ patients with high FIB-4 scores vs low FIB-4 scores at diagnosis had17:

- 78% higher all-cause medical cost ratio

- 12x increase in liver-related hospital admissions

- 33x higher liver-related costs

Healthcare costs increase incrementally with increasing FIB-4 scores. Annualized healthcare costs (in 2020 USD) for patients with the corresponding FIB-4 score at index are reported18,#:

| FIB-4 Score at Index** | ≤0.95 | >0.95 to ≤2.67 | >2.67 to ≤4.12 | >4.12 |

| Annualized healthcare costs (USD) | $16,744 | $19,637 | $25,728 | $34,667 |

According to this study, patients with MASH with a high FIB-4 score (>4.12) accrued twice the healthcare costs compared with patients with a low FIB-4 score (≤0.95).18

*According to estimates from a Markov model based on the assumption that approximately 20% of MASLD cases would be classified as NASH/MASH in 2015, corresponding to 3% of the adult population.10

†Based on a US population of 336 million and the assumptions that approximately 30% of cases would be classified as MASLD and 20% of these cases would be classified as MASH. In addition, estimates an F2 rate of 36% and F3 rate of 21%.7,10-12

‡Based on data collected from a large US healthcare dataset from October 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020, of patients with a MASH diagnosis. A total of 4989 patients were diagnosed, 4500 with noncirrhotic disease and 489 with cirrhotic disease. The mean costs in the study were estimated in December 2020 and adjusted for inflation to November 2023 USD (United States dollars).14

§Based on a retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis of employer-based insurance commercial claims conducted from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2016. The study included 153,323,509 individuals, out of whom 962,970 (0.6%) adults were diagnosed with MASH/MASLD and 428 (0.1%) had HCC. Adjusted healthcare costs for HCC were accounted for by adjusting for inflation from December 2016 USD to November 2023 USD.15

||The reported adjusted cost of liver transplants in 2023 is based on the total estimated number of transplants (8219) and estimated billed charges ($878,400) for the year 2020. Please note that these figures are subject to estimation and may not represent actual expenses.16

¶Based on an observational, retrospective study of 5104 adult patients with FIB-4 scores enrolled in commercial health plans or Medicare Advantage with ≥1 ICD-10 CM codes for MASLD or MASH between October 1, 2016, and May 31, 2022, which was the patient identification period. Data were analyzed against a reference group (ie, high FIB-4 score vs low FIB-4 score).17

#According to a retrospective, observational cohort study of 6743 adult patients with an EHR diagnosis of MASH from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2020. Costs including all-cause HCRU (including office visits, lab services, radiology services, and outpatient prescriptions) were recorded for the 6-month baseline and 6-month follow-up periods and combined into a single 12-month observation period. Costs were reported in 2020 USD.18

**FIB-4 was included as a continuous variable, reducing the uncertainty regarding the exact fibrosis stage while enabling the evaluation of the relationship between worsening fibrosis and healthcare costs.18

Publications

- Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Review. Sheka A C, Adeyi O, Thompson J, et al. JAMA. 2020, Mar. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2298.

- Mechanisms of Fibrosis Development in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Schwabe R F, Tabas I, Pajvani U B. Gastroenterology. 2020, May. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.311.

- Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis 2020. Tokushige K, Ikejima K, Ono M, et al. J Gastroenterol. 2021, Nov. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01796-x.

- Imaging Biomarkers of NAFLD, NASH, and Fibrosis. Ajmera V, Loomba R. Mol Metab. 2021, Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101167.

- Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors. Francque S, Szabo G, Abdelmalek M F, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00366-5.

-

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Cotter T G, Rinella M. Gastroenterology. 2020, May. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.052.

- Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Children. Xanthakos S A. Clin Liver Dis. 2022, Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2022.05.001.

-

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis After Liver Transplantation. Cotter T G, Charlton M. Liver Transpl. 2020, Jan. doi: 10.1002/lt.25657.

-

The Burden of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review of Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient-Reported Outcomes Younossi Z, Aggarwal P, Shrestha I, et al. JHEP Rep. 2022, Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100525.

-

Non-Invasive Diagnosis and Monitoring of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Tincopa M A, Loomba R. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, Jul. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00066-3.

-

American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice

Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver

Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. Endocr Pract. 2022, May. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010 -

Advanced Liver Fibrosis Is Common in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Followed in the Outpatient Setting: The Need for Systematic Screening Lomonaco R, Levia E G, Bril F, et al. Diabetes Care. 2021, Feb. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1997.

Novo Nordisk provided sponsorship for disease education. AMCP fully controls content of resource.

2. Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann Hepatol. 2023;29(1):101133.

3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases. Definition and Facts of NAFLD and NASH. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts

4. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Ong J, et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Most Rapidly Increasing Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(3):580-589.e5.

5. American Liver Foundation. NASH Complications. November 1, 2023. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://liverfoundation.org/liver-diseases/fatty-liver-disease/nonalcoholic-steatohepatitis-nash/nash-complications/.

6. Kanwal F, Shubrook JH, Younossi Z, et al. Preparing for the NASH Epidemic: A Call to Action. Metabolism. 2021;122:154822.

7. Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835.

8. Lazarus JV, Anstee QM, Hagström H, et al. Defining comprehensive models of care for NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(10):717-729. doi:10.1038/s41575-021-00477-7

9. American Liver Foundation. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. 2024. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://liverfoundation.org/liver-diseases/fatty-liver-disease/nonalcoholic-fatty-liver-disease-nafld/#:~:text=If%20NALFD%20begins%20to%20advance,Sometimes%20mental%20confusion%20can%20occur.

10. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123-133.

11. United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 22, 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/AGE295222

12. Shelley K, Articolo A, Luthra R, Charlton M. Clinical characteristics and management of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a real-world setting: analysis of the Ipsos NASH therapy monitor database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):160. doi:10.1186/s12876-023-02794-4

13. Younossi ZM, Paik JM, Henry L, et al. The growing economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;13(3):454-467.

14. Younossi Z, Mangla KK, Chandramouli AS, et al. Total healthcare cost and characteristics associated with higher change in cost in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Presented at the EASL International Liver Congress; June 22–26, 2022; London, United Kingdom.

15. Wong RJ, Kachru N, Martinez DJ, et al. Real-world comorbidity burden, health care utilization, and costs of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients with advanced liver diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(10):891-902.

16. Bentley TS, Ortner N. Milliman Report: 2020 U.S. organ and tissue transplants: Cost estimates, discussion, and emerging issues. January 2020.

17. Charlton M, Tonnu-Mihara I, Teng CC, et al. Health care resource utilization and cost burden of high disease severity in US adults with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a retrospective study. Presented at AASLD, The Liver Meeting® 2023; November 10–12, 2023; Boston, MA.

18. Tapper EB, Bonafede M, Fishman J, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs of care in the United States for patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):348-356.

Featured News & Resources

See Full CalendarAMCP Southwest Day of Education

Award Applications Open

News & Resources by Topic

AMCP offers a wide variety of educational opportunities, from events and webinars to online training.